Blood Suckers and Biting Insects

Bed Bugs

Bed bugs are parasites that preferentially feed on humans. If people aren't available, they instead will feed on other warm-blooded animals, including birds, rodents, bats, and pets. Bed bugs have been documented as pests since the 17th century. They were introduced into our country by the early colonists. Bed bugs were common in the United States prior to World War II, after which time widespread use of synthetic insecticides such as DDT greatly reduced their numbers. Improvements in household and personal cleanliness as well as increased regulation of the used furniture market also likely contributed to their reduced pest status. In the past decade, bed bugs have begun making a comeback across the United States, although they are not considered to be a major pest. The widespread use of baits rather than insecticide sprays for ant and cockroach control is a factor that has been implicated in their return. Bed bugs are blood feeders that do not feed on ant and cockroach baits. International travel and commerce are thought to facilitate the spread of these insect hitchhikers, because eggs, young, and adult bed bugs are readily transported in luggage, clothing, bedding, and furniture. Bed bugs can infest airplanes, ships, trains, and buses. Bed bugs are most frequently found in dwellings with a high rate of occupant turnover, such as hotels, motels, hostels, dormitories, shelters, apartment complexes, tenements, and prisons. Such infestations usually are not a reflection of poor hygiene or bad housekeeping.

Distribution

Bed bugs are fairly cosmopolitan. Cimex lectularius is most frequently found in the northern temperate climates of North America, Europe, and Central Asia, although it occurs sporadically in southern temperate regions. The tropical bed bug, C. hemipterus, is adapted for semitropical to tropical climates and is widespread in the warmer areas of Africa, Asia, and the tropics of North America and South America. In the United States, C. hemipterus occurs in Florida.

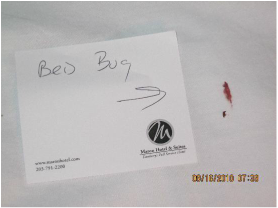

Identification

Adult bed bugs are brown to reddish-brown, oval-shaped, flattened, and about 3/16 to 1/5 inch long. Their flat shape enables them to readily hide in cracks and crevices. The body becomes more elongate, swollen, and dark red after a blood meal. Bed bugs have a beaklike piercing-sucking mouthpart system. The adults have small, stubby, nonfunctional wing pads. Newly hatched nymphs are nearly colorless, becoming brownish as they mature. Nymphs have the general appearance of adults. Eggs are white and about 1/32 inch long. Bed bugs superficially resemble a number of closely related insects (family Cimicidae), such as bat bugs (Cimex adjunctus), chimney swift bugs (Cimexopsis spp.), and swallow bugs (Oeciacus spp.). A microscope is needed to examine the insect for distinguishing characteristics, which often requires the skills of an entomologist. In Ohio, bat bugs are far more common than bed bugs.

Life Cycle

Female bed bugs lay from one to twelve eggs per day, and the eggs are deposited on rough surfaces or in crack and crevices. The eggs are coated with a sticky substance so they adhere to the substrate. Eggs hatch in 6 to 17 days, and nymphs can immediately begin to feed. They require a blood meal in order to molt. Bed bugs reach maturity after five molts. Developmental time (egg to adult) is affected by temperature and takes about 21 days at 86° F to 120 days at 65° F. The nymphal period is greatly prolonged when food is scarce. Nymphs and adults can live for several months without food. The adult's lifespan may encompass 12-18 months. Three or more generations can occur each year.

Habits

Bed bugs are fast moving insects that are nocturnal blood-feeders. They feed mostly at night when their host is asleep. After using their sharp beak to pierce the skin of a host, they inject a salivary fluid containing an anticoagulant that helps them obtain blood. Nymphs may become engorged with blood within three minutes, whereas a full-grown bed bug usually feeds for ten to fifteen minutes. They then crawl away to a hiding place to digest the meal. When hungry, bed bugs again search for a host. Bed bugs hide during the day in dark, protected sites. They seem to prefer fabric, wood, and paper surfaces. They usually occur in fairly close proximity to the host, although they can travel far distances. Bed bugs initially can be found about tufts, seams, and folds of mattresses, later spreading to crevices in the bedstead. In heavier infestations, they also may occupy hiding places farther from the bed. They may hide in window and door frames, electrical boxes, floor cracks, baseboards, furniture, and under the tack board of wall-to-wall carpeting. Bed bugs often crawl upward to hide in pictures, wall hangings, drapery pleats, loosened wallpaper, cracks in plaster, and ceiling moldings.

Injury

The bite is painless. The salivary fluid injected by bed bugs typically causes the skin to become irritated and inflamed, although individuals can differ in their sensitivity. A small, hard, swollen, white welt may develop at the site of each bite. This is accompanied by severe itching that lasts for several hours to days. Scratching may cause the welts to become infected. The amount of blood loss due to bed bug feeding typically does not adversely affect the host. Rows of three or so welts on exposed skin are characteristic signs of bed bugs. Welts do not have a red spot in the center such as is characteristic of flea bites. Some individuals respond to bed bug infestations with anxiety, stress, and insomnia. Bed bugs are not known to transmit disease. They have been found with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus(MRSA) and with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faeciumVRE), but the significance of this is still unknown. Bed bugs are attracted to their hosts primarily by carbon dioxide , secondly by warmth, and also by certain chemicals. Bedbugs prefer exposed skin, preferably the face, neck and arms of a sleeping person. Melnick, Meredith (2011-05-12). "Study: Bedbugs May Carry MRSA; Germ Transmission Unclear | TIME.com". Healthland.time.com. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

Tell-tale Signs

A bed bug infestation can be recognized by blood stains from crushed bugs or by rusty (sometimes dark) spots of excrement on sheets and mattresses, bed clothes, and walls. Fecal spots, eggshells, and shed skins may be found in the vicinity of their hiding places. An offensive, sweet, musty odor from their scent glands may be detected when bed bug infestations are severe.

Control Measures

A critical first step is to correctly identify the blood-feeding pest, as this determines which management tactics to adopt that take into account specific bug biology and habits. For example, if the blood-feeder is a bat bug rather than a bed bug, a different management approach is needed. Control of bed bugs is best achieved by following an integrated pest

management (IPM) approach that involves multiple tactics, such as preventive measures, sanitation, and chemicals applied to targeted sites. Severe infestations usually are best handled by a licensed pest management professional.

Prevention

Do not bring infested items into one's home. It is important to carefully inspect clothing and baggage of travelers, being on the lookout for bed bugs and their tell-tale fecal spots. Also, inspect secondhand beds, bedding, and furniture. Caulk cracks and crevices in the building exterior and also repair or screen openings to exclude birds, bats, and rodents that can serve as alternate hosts for bed bugs.

Inspection

A thorough inspection of the premises to locate bed bugs and their harborage sites is necessary so that cleaning efforts and insecticide treatments can be focused. Inspection efforts should concentrate on the mattress, box springs, and bed frame, as well as crack and crevices that the bed bugs may hide in during the day or when digesting a blood meal. The latter sites include window and door frames, floor cracks, carpet tack boards, baseboards, electrical boxes, furniture, pictures, wall hangings, drapery pleats, loosened wallpaper, cracks in plaster, and ceiling moldings. Determine whether birds or rodents are nesting on or near the house. In hotels, apartments, and other multiple-type dwellings, it is advisable to also inspect adjoining units since bed bugs can travel long distances.

Sanitation

Sanitation measures include frequently vacuuming the mattress and premises, laundering bedding and clothing in hot water, and cleaning and sanitizing dwellings. After vacuuming, immediately place the vacuum cleaner bag in a plastic bag, seal tightly, and discard in a container outdoors-this prevents captured bed bugs from escaping into the home. A stiff brush can be used to scrub the mattress seams to dislodge bed bugs and eggs. Discarding the mattress is another option, although a new mattress can quickly become infested if bed bugs are still on the premises. Steam cleaning of mattresses generally is not

recommended because it is difficult to get rid of excess moisture, which can lead to problems with mold, mildew, house dust mites, etc. Repair cracks in plaster and glue down loosened wallpaper to eliminate bed bug harborage sites. Remove and destroy wild animal roosts and nests when possible.

Trapping

After the mattress is vacuumed or scrubbed, it can be enclosed in a zippered mattress cover such as that used for house dust mites. Any bed bugs remaining on the mattress will be trapped inside the cover. Leave the cover in place for a year or so since bed bugs can live for a long time without a blood meal. Sticky traps or glue boards may be used to capture bed bugs that wander about. However, the effectiveness of these traps is not well documented.

Bed bugs are parasites that preferentially feed on humans. If people aren't available, they instead will feed on other warm-blooded animals, including birds, rodents, bats, and pets. Bed bugs have been documented as pests since the 17th century. They were introduced into our country by the early colonists. Bed bugs were common in the United States prior to World War II, after which time widespread use of synthetic insecticides such as DDT greatly reduced their numbers. Improvements in household and personal cleanliness as well as increased regulation of the used furniture market also likely contributed to their reduced pest status. In the past decade, bed bugs have begun making a comeback across the United States, although they are not considered to be a major pest. The widespread use of baits rather than insecticide sprays for ant and cockroach control is a factor that has been implicated in their return. Bed bugs are blood feeders that do not feed on ant and cockroach baits. International travel and commerce are thought to facilitate the spread of these insect hitchhikers, because eggs, young, and adult bed bugs are readily transported in luggage, clothing, bedding, and furniture. Bed bugs can infest airplanes, ships, trains, and buses. Bed bugs are most frequently found in dwellings with a high rate of occupant turnover, such as hotels, motels, hostels, dormitories, shelters, apartment complexes, tenements, and prisons. Such infestations usually are not a reflection of poor hygiene or bad housekeeping.

Distribution

Bed bugs are fairly cosmopolitan. Cimex lectularius is most frequently found in the northern temperate climates of North America, Europe, and Central Asia, although it occurs sporadically in southern temperate regions. The tropical bed bug, C. hemipterus, is adapted for semitropical to tropical climates and is widespread in the warmer areas of Africa, Asia, and the tropics of North America and South America. In the United States, C. hemipterus occurs in Florida.

Identification

Adult bed bugs are brown to reddish-brown, oval-shaped, flattened, and about 3/16 to 1/5 inch long. Their flat shape enables them to readily hide in cracks and crevices. The body becomes more elongate, swollen, and dark red after a blood meal. Bed bugs have a beaklike piercing-sucking mouthpart system. The adults have small, stubby, nonfunctional wing pads. Newly hatched nymphs are nearly colorless, becoming brownish as they mature. Nymphs have the general appearance of adults. Eggs are white and about 1/32 inch long. Bed bugs superficially resemble a number of closely related insects (family Cimicidae), such as bat bugs (Cimex adjunctus), chimney swift bugs (Cimexopsis spp.), and swallow bugs (Oeciacus spp.). A microscope is needed to examine the insect for distinguishing characteristics, which often requires the skills of an entomologist. In Ohio, bat bugs are far more common than bed bugs.

Life Cycle

Female bed bugs lay from one to twelve eggs per day, and the eggs are deposited on rough surfaces or in crack and crevices. The eggs are coated with a sticky substance so they adhere to the substrate. Eggs hatch in 6 to 17 days, and nymphs can immediately begin to feed. They require a blood meal in order to molt. Bed bugs reach maturity after five molts. Developmental time (egg to adult) is affected by temperature and takes about 21 days at 86° F to 120 days at 65° F. The nymphal period is greatly prolonged when food is scarce. Nymphs and adults can live for several months without food. The adult's lifespan may encompass 12-18 months. Three or more generations can occur each year.

Habits

Bed bugs are fast moving insects that are nocturnal blood-feeders. They feed mostly at night when their host is asleep. After using their sharp beak to pierce the skin of a host, they inject a salivary fluid containing an anticoagulant that helps them obtain blood. Nymphs may become engorged with blood within three minutes, whereas a full-grown bed bug usually feeds for ten to fifteen minutes. They then crawl away to a hiding place to digest the meal. When hungry, bed bugs again search for a host. Bed bugs hide during the day in dark, protected sites. They seem to prefer fabric, wood, and paper surfaces. They usually occur in fairly close proximity to the host, although they can travel far distances. Bed bugs initially can be found about tufts, seams, and folds of mattresses, later spreading to crevices in the bedstead. In heavier infestations, they also may occupy hiding places farther from the bed. They may hide in window and door frames, electrical boxes, floor cracks, baseboards, furniture, and under the tack board of wall-to-wall carpeting. Bed bugs often crawl upward to hide in pictures, wall hangings, drapery pleats, loosened wallpaper, cracks in plaster, and ceiling moldings.

Injury

The bite is painless. The salivary fluid injected by bed bugs typically causes the skin to become irritated and inflamed, although individuals can differ in their sensitivity. A small, hard, swollen, white welt may develop at the site of each bite. This is accompanied by severe itching that lasts for several hours to days. Scratching may cause the welts to become infected. The amount of blood loss due to bed bug feeding typically does not adversely affect the host. Rows of three or so welts on exposed skin are characteristic signs of bed bugs. Welts do not have a red spot in the center such as is characteristic of flea bites. Some individuals respond to bed bug infestations with anxiety, stress, and insomnia. Bed bugs are not known to transmit disease. They have been found with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus(MRSA) and with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faeciumVRE), but the significance of this is still unknown. Bed bugs are attracted to their hosts primarily by carbon dioxide , secondly by warmth, and also by certain chemicals. Bedbugs prefer exposed skin, preferably the face, neck and arms of a sleeping person. Melnick, Meredith (2011-05-12). "Study: Bedbugs May Carry MRSA; Germ Transmission Unclear | TIME.com". Healthland.time.com. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

Tell-tale Signs

A bed bug infestation can be recognized by blood stains from crushed bugs or by rusty (sometimes dark) spots of excrement on sheets and mattresses, bed clothes, and walls. Fecal spots, eggshells, and shed skins may be found in the vicinity of their hiding places. An offensive, sweet, musty odor from their scent glands may be detected when bed bug infestations are severe.

Control Measures

A critical first step is to correctly identify the blood-feeding pest, as this determines which management tactics to adopt that take into account specific bug biology and habits. For example, if the blood-feeder is a bat bug rather than a bed bug, a different management approach is needed. Control of bed bugs is best achieved by following an integrated pest

management (IPM) approach that involves multiple tactics, such as preventive measures, sanitation, and chemicals applied to targeted sites. Severe infestations usually are best handled by a licensed pest management professional.

Prevention

Do not bring infested items into one's home. It is important to carefully inspect clothing and baggage of travelers, being on the lookout for bed bugs and their tell-tale fecal spots. Also, inspect secondhand beds, bedding, and furniture. Caulk cracks and crevices in the building exterior and also repair or screen openings to exclude birds, bats, and rodents that can serve as alternate hosts for bed bugs.

Inspection

A thorough inspection of the premises to locate bed bugs and their harborage sites is necessary so that cleaning efforts and insecticide treatments can be focused. Inspection efforts should concentrate on the mattress, box springs, and bed frame, as well as crack and crevices that the bed bugs may hide in during the day or when digesting a blood meal. The latter sites include window and door frames, floor cracks, carpet tack boards, baseboards, electrical boxes, furniture, pictures, wall hangings, drapery pleats, loosened wallpaper, cracks in plaster, and ceiling moldings. Determine whether birds or rodents are nesting on or near the house. In hotels, apartments, and other multiple-type dwellings, it is advisable to also inspect adjoining units since bed bugs can travel long distances.

Sanitation

Sanitation measures include frequently vacuuming the mattress and premises, laundering bedding and clothing in hot water, and cleaning and sanitizing dwellings. After vacuuming, immediately place the vacuum cleaner bag in a plastic bag, seal tightly, and discard in a container outdoors-this prevents captured bed bugs from escaping into the home. A stiff brush can be used to scrub the mattress seams to dislodge bed bugs and eggs. Discarding the mattress is another option, although a new mattress can quickly become infested if bed bugs are still on the premises. Steam cleaning of mattresses generally is not

recommended because it is difficult to get rid of excess moisture, which can lead to problems with mold, mildew, house dust mites, etc. Repair cracks in plaster and glue down loosened wallpaper to eliminate bed bug harborage sites. Remove and destroy wild animal roosts and nests when possible.

Trapping

After the mattress is vacuumed or scrubbed, it can be enclosed in a zippered mattress cover such as that used for house dust mites. Any bed bugs remaining on the mattress will be trapped inside the cover. Leave the cover in place for a year or so since bed bugs can live for a long time without a blood meal. Sticky traps or glue boards may be used to capture bed bugs that wander about. However, the effectiveness of these traps is not well documented.

Bed Bug Identity, Bites and Fecal Stains

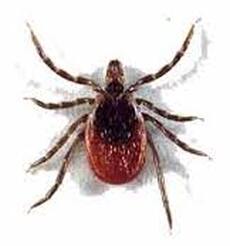

Ticks

American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

The American dog tick is the most commonly encountered species throughout Ohio.

Identification:

Adults typically are brownish with light grey mottling on the scutum. Immatures are very small and rarely observed. The adult American dog tick is the largest tick in Ohio at approximately 3/16 inch (unfed females, fed, and unfed males). After feeding, the female is much larger (~5/8 inches long) and mostly gray.

Biology:

American dog ticks prefer grassy areas along roads and paths, particularly next to woody or shrubby habitats. The immature stages of this species feed on rodents and other small mammals. Adult ticks feed on a wide variety of medium to large size mammals such as opossums, raccoons, groundhogs, dogs, and humans. Adults are most commonly encountered by humans and pets. Adults are active during spring and summer, but they are most abundant from mid-April to mid-July. The adult tick waits on grass and weeds for a suitable host to brush against the vegetation. It then clings to the host’s fur or clothing and crawls upward seeking a place to attach and feed. Attached American dog ticks are frequently found on the scalp and hairline at the back of the neck. Males obtain a small blood meal then mate with the female while she is attached to the host. The female feeds for 7 to 11 days then drops to the ground and remains there for several days before laying approximately 6,000 eggs then dying shortly thereafter. The male remains on the host and continues to feed and mate for the remainder of the season until his death.

Diseases:

The American dog tick is the primary transmitter of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF). This species may also transmit tularemia. Toxins in the tick’s injected saliva have been known to cause tick paralysis in dogs and humans. Immediate tick removal usually results in a quick recovery.

Blacklegged Tick or Deer Tick (Ixodes scapularis)

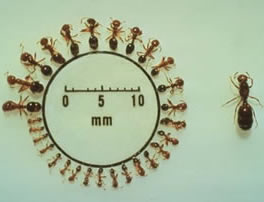

The blacklegged tick recently has emerged as a serious pest in Ohio. This species has become much more common in the state since 2010, particularly in regions with the tick’s favored forest habitat. Maps showing Ohio counties with the blacklegged tick are available at http://www.odh.ohio.gov/. Various stages of the blacklegged tick, clockwise from left to right: unfed larva, unfed nymph, fed nymph, adult male, adult female, partly fed female, and fully engorged.

Identification:

The larval stage of the blacklegged tick is extremely tiny and nearly translucent, which makes it extremely difficult to see. The nymphal stage is translucent to slightly gray or brown. Adult males are slightly more than 1/16 inches long; unfed females are larger (~3/32 inches long). Both sexes are dark chocolate brown, but the rear half of the adult female is red or orange. Engorged adult females may appear gray. All comparable stages of the blacklegged tick are relatively smaller than other medically important ticks.

Biology:

Blacklegged ticks are found mostly in or near forested areas. The immature stages feed on a wide range of hosts that occur in their woodland habitats. Adult blacklegged ticks feed on large mammals, most commonly white-tailed deer. Hence, some people call them ‘deer ticks.’ Mating can occur on or off of a host. The female deposits approximately 2,000 eggs, all in one location. All stages may attach to humans. They have no site attachment preference and will attach almost immediately upon encountering bare human skin. One or more life stages may be active during every month of the year depending on temperature. Because of this year-long activity, preventative measures should be taken outdoors where the tick occurs, even during autumn and winter.

Diseases:

The blacklegged tick is the only vector of Lyme disease in the eastern and midwestern U.S. It is also the principal vector of human granulocytic anaplasmosis and babesiosis. This tick species may be co-infected with several disease agents, and some ticks may

simultaneously infect a host with two or more of these diseases.

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum)

Lone star ticks recently have emerged as a serious pest, especially in southern Ohio.

Identification:

The unfed adult female is about 3/16 inches long, brown, with a distinctive silvery spot on the upper surface of the scutum (hence the name ‘lone star.’). Once fed, the female is almost circular in shape and ~7/16 inches long. The male tick is about 3/16 inches long, brown, with whitish markings along the rear edge.

Biology:

Lone star ticks are most commonly found in southern Ohio, but they are dispersed by migratory birds and therefore are reported in most Ohio counties. All stages readily feed on almost any bird or mammal, including humans. All stages can be found throughout the warm months of the year. Shade is an important environmental factor for this species, which typically occurs in shady locations along roadsides and meadows and in grassy and shrubby habitats. All stages crawl to the tip of low growing vegetation and wait for a host to pass by. Larval lone star ticks, commonly referred to as seed ticks, may congregate in large numbers on vegetation. A person or pet unlucky enough to brush against this vegetation may become host to hundreds of larval ticks. The sticky side of masking tape can be used to collect crawling immatures.

Diseases:

Lone star ticks are the primary transmitter of human monocytic ehrlichiosis and southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI). They also may transmit tularemia and Q-fever.

Brown Dog Tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus)

The brown dog tick, although very uncommon in Ohio, is the only tick that can become established indoors in homes with dogs and in kennels.

Identification:

The adult brown dog tick is reddish brown and lacks markings. Unfed adults are about 1/8 inches long. After feeding, the female is much larger (~1/2 inches long) and bluish gray.

Biology:

Unlike other tick species, the brown dog tick can complete its entire life cycle indoors. It is well adapted to survive in the warm, dry conditions inside and outside home environments. These ticks do not thrive in wooded areas. Nonetheless, they may occur in grassy and bushy areas adjacent to homes and kennels, roadsides, and footpaths. Brown dog ticks rarely feed on humans. Rather, dogs are their preferred host. All stages of the brown dog tick feed on dogs and they may attach anywhere on a dog’s body. However, adult ticks typically attach on the dog’s ears and between its toes, whereas larvae and nymphs typically attach on the dog’s back. After feeding, they drop off the host but do not travel far. Brown dog ticks can complete a generation in approximately 60 days with optimal temperatures and readily available dog hosts.

Diseases:

In Ohio, the brown dog tick has not been implicated in human disease transmission. However, this tick species has been identified as a transmitter of RMSF to humans in the southwestern U.S. and along the U.S.-Mexico border. It currently is not known if the brown dog tick serves as a vector of RMSF in other parts of the U.S. Nationwide, the brown dog tick is an important, but uncommon, transmitter of RMSF and several other disease organisms to dogs.

Management:

For most tick species, outdoor chemical control is largely ineffective because of their wide distribution and movement, but the brown dog tick is an exception because of its close proximity to human habitation. Treatment of the premises outside the home

should include grassy and brushy areas around outbuildings and kennels, sites where the dog rests, and underneath doghouses where ticks may reside during off-host periods. Pesticide treatments should be preceded by sanitation efforts such as vacuuming and cleaning to remove debris and as many ticks as possible; this also allows increased penetration of an insecticide into cracks and crevices. Pesticide application indoors should target areas frequented by the dog, particularly its sleeping and resting sites where ticks are likely to have dropped off. Because ticks hide in secluded places to molt, it also is critical to treat cracks and crevices in the floor and walls, baseboards, window frames, and doorframes; around wall molding and hangings; and under carpet edges. The dog should be treated for ticks, preferably by a veterinarian, at the same time as the premises, outdoors or indoors, are being treated. A variety of pesticide products are labeled for indoor and outdoor treatment of ticks.

Tick-Borne Diseases in Ohio

Tick feeding often results in inflammation, swelling, irritation, and the potential for secondary bacterial infection at the feeding

site. However, infection by tick-borne disease agents during feeding is of primary concern. Humans and pets can become infected with causal agents of RMSF, Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, human monocytic ehrlichiosis, tularemia, and babesiosis among others. If you experience fever or flu-like symptoms following a tick bite, immediately contact your healthcare professional and emphasize that you recently were bitten by a tick. Save the tick in some type of container and take it with you to the healthcare professional. It is very important to receive the appropriate antibiotics as soon as possible.

Pets, especially dogs that become infected with a tick-borne disease, may become lethargic and anemic. They may quit eating and lose weight, and they sometimes become lame. Any pet with such symptoms should be examined by a veterinarian. When heavily infested with ticks, excessive blood loss can result in the pet’s death. Dogs should be routinely tested for exposure to tick-borne diseases at annual checkups, but immediately if symptoms occur.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

RMSF is not confined to the Rocky Mountain range, despite the name of the disease, and cases are reported in Ohio each year. This disease is transmitted by adult American dog ticks. Less than 2% of these ticks carry the causative bacterial agent, Rickettsia

rickettsii, hence, relatively few people are infected. Furthermore, an infected tick must be attached for at least a day for transmission to occur. Symptoms of RMSF appear 3 to 12 days after tick feeding and typically include sudden high fever, headache, and aching muscles. On the second or third day of the fever, a non-itchy rash may develop on the wrists and ankles. The rash soon spreads to other parts of the body including the torso, palms, and soles. This disease rapidly progresses and can cause death if not treated with the appropriate antibiotics. Early treatment of RMSF typically results in rapid recovery. Most fatalities, although rare, can be attributed to a delay in seeking medical attention.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is transmitted by the blacklegged tick and is the most prevalent tick-borne disease of humans in Ohio and the U.S. This bacterial disease is named after Lyme, Connecticut, where cases were first reported in 1975. The nymphal stage of the blacklegged tick is usually responsible for transmitting Lyme disease, which is caused by the bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi.

Symptoms may include a bull’s-eye rash developing at the site of a tick bite within 2 to 32 days. This rash is diagnostic for Lyme disease. However, up to 40% of infected humans do not develop a ring-rash, which is almost always more than 2-3 inches across. Fever, headache, fatigue, or joint pain also may be symptoms of Lyme disease. Immediate antibiotic therapy for Lyme disease reduces the risk of neurological, arthritic, or cardiac complications developing days to years later. Dogs are susceptible to Lyme disease. Precautions should be taken to protect them from tick exposure. Although cats are not susceptible to Lyme disease, they are particularly likely to pick up blacklegged ticks and transport them into the home environment. Before using any over-the-counter product, it is recommended that you consult your veterinarian.

Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis (Anaplasmosis)

Anaplasmosis is transmitted by blacklegged tick nymphs and adults and is less commonly reported than Lyme disease in Ohio. This disease is caused by the bacterium, Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Onset of symptoms may begin up to three weeks after a blacklegged tick bite. Initial symptoms may include fever, headache, and muscle aches. Other symptoms may include nausea, joint pain, chills, confusion, and sometimes a rash. Anaplasmosis may cause severe illness, especially if left untreated, and 50% of

all infected individuals require hospitalization.

Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichiosis)

Ehrlichiosis is transmitted by lone star tick nymphs and adults. Several species of Ehrlichia bacteria cause ehrlichiosis. The symptoms of ehrlichiosis are the same as for anaplasmosis (see above).

Life Cycle and Habits

Ticks have a life cycle that includes the egg and three stages: six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and eight-legged adult. Adult ticks often have distinct characteristics and markings, but immature stages (larvae and nymphs) are entirely tan or brown and difficult to identify to species. All stages are round to oval shaped. Ticks must consume blood at every stage to develop. Most species feed on a different type of host during the adult stage, with larvae and nymphs preferring smaller hosts. Nymphs become engorged, but they are much smaller than the adults. Adult female ticks greatly increase in size during feeding but adult males do not.

Integrated Pest Management Strategies

Prevention of Tick Bites

Humans

- Apply a tick repellent, making sure to follow the manufacturer’s instructions. Note that DEET formulations of at least 25% are needed to repel ticks. Repellents containing permethrin should be applied to clothing only; do not apply directly to exposed skin.

- Wear light-colored clothing to make it easier to find crawling ticks.

- Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants. Tuck pants into socks, and tuck shirt into pants.

- Perform tick checks frequently.

- Remove ticks immediately.

- Avoid tall grass and weedy areas; stay on paths.

- Protect pets with a reputable anti-tick product.

- Lyme disease vaccination of dogs in Ohio should be considered as infection risk increases.

- Keep dogs confined to your yard or home; do not allow them to roam freely.

- Keep dogs on a leash during walks, and inspect them for ticks afterwards.

- Avoid tall grass and weedy areas; stay on paths.

Habitat management is essential for controlling tick populations. Keep your yard mowed, and do not allow brush or leaf litter to

accumulate. Remove brush, tall weeds, and grass in order to eliminate the habitat of rodents and other small mammals, which serve as hosts for ticks.

Host Removal

It is helpful to remove rodents harboring inside or near one’s house by using traps or rodenticides.

Insecticide Treatment of Pets

Dogs may be treated for ticks, and products are available from your veterinarian. Before using any over-the-counter product, it is

recommended that you consult your veterinarian.

Tick Group Identification after Gorging Themselves

Mosquito Female Sucking Blood after Mating

Mosquito Female Sucking Blood after Mating

Mosquito

Only female mosquitoes bite animals and drink blood. Male mosquitoes do not bite, but feed on the nectar of flowers.

Aedes mosquitoes are painful and persistent biters, attacking during daylight hours (not at night). They do not enter dwellings, and they prefer to bite mammals like humans. Aedes mosquitoes are strong fliers and are known to fly many miles from their breeding sources. Culex mosquitoes are painful and persistent biters also, but prefer to attack at dusk and after dark, and readily enter dwellings for blood meals.

Domestic and wild birds are preferred over man, cows, and horses. Culex tarsalis is known to transmite ncephalitis (sleeping sickness) to man and horses. Culex are generally weak fliers and do not move far from home, although they have been known to fly up to two miles. Culex usually live only a few weeks during the warm summer months. Those females which emerge in late summer search for sheltered areas where they "hibernate" until spring. Warm weather brings her out in search of water on which to lay her eggs. Culiseta mosquitoes are moderately aggressive biters, attacking in the evening hours or in shade during the day. Anopheles mosquitoes are the only mosquito which transmits malaria to man.

Habits and Habitat

The period of development from egg to adult varies among species and is strongly influenced by ambient temperature. Some species of mosquitoes can develop from egg to adult in as few as five days, but a more typical period of development in tropical conditions would be some 40 days or more for most species. The variation of the body size in adult mosquitoes depends on the density of the larval population and food supply within the breeding water. Adult mosquitoes usually mate within a few days after emerging from the pupal stage. In most species, the males form large swarms, usually around dusk, and the females fly into the swarms to mate. Males typically live for about a week, feeding on nectar and other sources of sugar. After obtaining a full blood meal, the female will rest for a few days while the blood is digested and eggs are developed. This process depends on the temperature, but usually takes two to three days in tropical conditions. Once the eggs are fully developed, the female lays them and resumes host-seeking. The cycle repeats itself until the female dies. While females can live longer than a month in captivity, most do not live longer than one to two weeks in nature. Their lifespans depend on temperature, humidity, and their ability to successfully obtain a blood meal while avoiding host defenses and predators. Some female mosquitoes prefer to feed on only one type of animal or they can feed on a variety of animals. Female mosquitoes feed on man, domesticated animals, such as cattle, horses, goats, etc; all types of birds including chickens; all types of wild animals including deer, rabbits; and they also feed on snakes, lizards, frogs, and toads.

Life Cycle

The mosquito goes through four separate and distinct stages of its life cycle and they are as follows: Egg, Larva, pupa, and adult. Each of these stages can be easily recognized by their special appearance. There are four common groups of mosquitoes living in the Bay Area. They are Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, and Culiseta.

Egg :

Eggs are laid one at a time and they float on the surface of the water. In the case of Culex and Culiseta species, the eggs are stuck together in rafts of a hundred or more eggs. Anopheles and Aedes species do not make egg rafts but lay their eggs separately. Culex, Culiseta, and Anopheles lay their eggs on water while Aedes lay their eggs on damp soil that will be flooded by water. Most eggs hatch into larvae within 48 hours.

Larva :

The larva (larvae - plural) live in the water and come to the surface to breathe. They shed their skin four times growing larger after each molting. Most larvae have siphon tubes for breathing and hang from the water surface. Anopheles larvae do not have a siphon and they lay parallel to the water surface. The larva feed on micro-organisms and organic matter in the water. On the fourth molt the larva changes into a pupa.

Pupa:

The pupal stage is a resting, non-feeding stage. This is the time the mosquito turns into an adult. It takes about two days before the adult is fully developed. When development is complete, the pupal skin splits and the mosquito emerges as an adult.

Adult:

The newly emerged adult rests on the surface of the water for a short time to allow itself to dry and all its parts to harden. Also, the wings have to spread out and dry properly before it can fly. The egg, larvae and pupae stages depend on temperature and species characteristics as to how long it takes for development. For instance, Culex tarsalis might go through its life cycle in 14 days at 70 F and take only 10 days at 80 F. Also, some species have naturally adapted to go through their entire life cycle in as little as four days or as long as one month.

Mosquito Identity, Breeding Areas and Bite

Head Louse

Head Louse

Head Lice

The head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) is an obligate ectoparasite. Head lice are wingless insects spending their entire life on the human scalp and feeding exclusively on human blood. Humans are the only known hosts of this specific parasite, while chimpanzees host a closely related species, Pediculus schaeffi. Other species of lice infest most orders of mammals and all orders of birds. Like all lice, head lice differ from other hematophagic ectoparasites such as the flea in that lice spend their entire life cycle on a host. Head lice cannot fly, and their short stumpy legs render them incapable of jumping, or even walking efficiently on flat surfaces. Head lice infect hair on the head. Tiny eggs on the hair look like flakes of dandruff. However, instead of flaking off the scalp, they stay put. Head lice can live up to 30 days on a human. Their eggs can live for more than 2 weeks. Head lice spread easily, particularly among school children. Head lice are more common in close overcrowded living conditions. Come in close contact with a person who has lice. Touch the clothing or bedding of someone who has lice. Share hats, towels, brushes, or combs of someone who has had lice. Having head lice causes intense itching, but does not lead to serious medical problems. Unlike body lice,head lice never carry or spread diseases.

The body louse (Pediculus humanus humanus, sometimes called Pediculus humanus corporis) is a louse that infests humans. The condition of being infested with head lice, body lice, or pubic lice is known as pediculosis. Adult body lice are 2.3–3.6 mm in length. Body lice live and lay eggs on clothing and only move to the skin to feed. Body lice are known to spread disease. Body lice infestations (pediculosis) are spread most commonly by close person-to-person contact but are generally limited to persons who live under conditions of crowding and poor hygiene (for example, the homeless, refugees, etc.). Dogs, cats, and other pets do not play a role in the transmission of human lice. Body lice can spread epidemic typhus, trench fever, and louse-borne relapsing fever. Although louse-borne (epidemic) typhus is no longer widespread, outbreaks of this disease still occur during times of war, civil unrest, natural or man-made disasters, and in prisons where people live together in unsanitary conditions. Louse-borne typhus still exists in places where climate, chronic poverty, and social customs or war and social upheaval prevent regular changes and laundering of clothing.

Body Louse and Head Louse Identity

Chiggers

Once a chigger has started to inject digestive enzymes into a person's skin, often within one to three hours, the person begins to experience symptoms.

Chiggers are the juvenile, or larvae, form of a type of mite belonging to the family, 'Trombiculidae', (also called berry bugs, harvest mites, red bugs or scrub-itch mites). The mites are arachnids, such as ticks or spiders, and can be found throughout the world. Chiggers live most commonly in grassy fields, forests, parks, gardens, as well as in areas that are moist, such as near rivers or lakes. The majority of chigger larvae that cause bites can be found on plants that are fairly close to the ground because they need a high-level of humidity in order to survive. Chiggers are hard to see with the naked eye due to their length; they are less than 1/150th of an inch long. Chiggers are red and are easiest to see when they are present in clusters on a person's skin. Juvenile chiggers have six legs, while the adults have eight.

Chigger larvae attack everyone from picnickers and campers to bird watchers and berry pickers. They are found in the largest numbers in early summer when weeds, grass, and other forms of vegetation are at their heaviest. Chiggers do not burrow in a person's skin; instead, they insert their mouth-parts into a person's skin pore or hair follicle. The bites create small, red-colored welts on the person's skin that are accompanied by an intense itching similar that that experienced with poison sumac or poison ivy. The symptoms of a chigger bite are many times the only way of learning that an outdoor area is infested with the creatures because they are so small. Chiggers also bite a number of animals such as turtles, snakes, birds, and smaller mammals.

Adult chiggers spend the winter either near, or slightly below, the surface of the ground or other protected places. Female chiggers become active in the Spring time, laying up to fifteen eggs each day in vegetation when soil temperatures reach sixty degrees or more. The eggs hatch into six-legged larvae capable of biting human beings. Once they have hatched, chigger larvae climb onto vegetation and seek a host to bite. Once they have fed, the larvae drop off of their host and transform into eight-legged nymphs which then develop into adult chiggers. Both nymphs and adults eat the eggs of isopods, springtails, and mosquitoes. The life cycle of chiggers is approximately fifty to seventy days, with adult female chiggers living up to a year and producing offspring for the duration of their lives. Multiple generations of chiggers are hatched in climates that are warmer, although only two or three develop each season in more northern states. Chiggers are commonly encountered in the late spring and summer.

Chigger bite

The larvae of chiggers do not burrow into a person's skin; they also do not suck a person's blood. Chigger larvae pierce a person's skin and inject the person with a salivary secretion that contains powerful digestive enzymes. The enzymes break down skin cells that the larvae ingests; the tissues become liquefied and the larvae sucks the tissues up. The digestive fluid also causes surrounding tissues to harden and form a straw-like tube of hardened flesh called a, 'stylostome,' which the larvae uses to suck further digested skin cells through.The larvae feeds for four days, and once it has fully-fed, it drops from its host, leaving a red welt with a hard, white center on the skin that itches severely and has the potential to develop dermatitis. Swelling, itching, welts, or fever can continue for a week or longer. Scratching a bite, or breaking the skin, can result in a secondary infection. Fortunately, chiggers are not known to spread any forms of disease in America. The majority of chigger bites occur around a person's ankles, groin, crotch area, in a person's arm pits, or behind the person's knees. Barriers to migration on a person's skin, such as belts, might be one reason why chigger bites are also common around a person's waist, or in other areas of a person's body where migration is prevented due to compression from clothing.

The bite from a chigger itself is something that is not noticeable. Once a chigger has started to inject digestive enzymes into a person's skin, often within one to three hours, the person begins to experience symptoms.

The symptoms of a chigger bite can include the following:

- Pronounced itching

- The itching persists for several days

- The itch is due to the presence of the stylostome

- The area of the bite may be reddened, flat, or raised

- The itch is usually most intense within 1-2 days after the bite

- Complete resolution of the skin lesions can take up to two weeks

Many of the home remedies for chigger bites are based upon the belief that chiggers somehow burrow into and remain in a person's skin; these beliefs are incorrect. People have applied alcohol, nail polish, and bleach to bites in attempts to somehow suffocate or kill chiggers. Due to the fact that chiggers are not present in the person's skin, these remedies are not effective in the slightest.

Treatment for chigger bites is directed towards relieving the itching and inflammation the person is experiencing. Corticosteroid creams and calamine lotion can be used to control the itching. Oral antihistamines such as diphenhydramine can also be used to provide relief.

When a person returns from a chigger-infested area they should wash their clothing in hot, soapy water for around a half an hour. The infested clothing should not be worn again until they are washed appropriately or exposed to hot sunshine. Clothes that have not been washed, or clothes that have been washed in cold water, will still contain chiggers and re-infest a person's skin. It is important for the person to take a hot bath or shower and wash with soap repeatedly. The chiggers might be dislodged from the person's skin, but the person will still have the stylostomes that cause the severe itching.

Deep scratching with the intention of removing stylostomes may cause a person to contract a secondary infection. To temporarily relieve itching, apply benzocaine, calamine lotion, or hydrocortisone cream. Some people use cold cream, Vaseline, or baby oil. Chigger bites do not cause any long-term complications of themselves. Prolonged itching and scratching can lead to skin wounds that have the potential to become infected.

Preventing Chiggers

To help prevent the presence of chiggers, mow weeds, briar's, lawns, thick vegetation, and eliminate moisture and shade. Doing so will reduce the populations of chiggers. Allow sunlight and air to circulate freely. Chigger larvae have the ability to penetrate a number of types of clothing, but high boots and trousers made of tightly-woven fabric that is tucked into stocking or boots can help in deterring them. Before you enter an area where you know chiggers are present, protect yourself by using a repellent such as DEET, Off, Detamide, Repel, or another form of insecticide. Apply the repellent to your skin and your clothing, particularly your arms, hands, and legs - as well as opening in your clothing. Keep moving since the worst chigger infestations happen when you are sitting or laying down.

Biting Midge after a Blood Meal

Biting Midge after a Blood Meal

Biting Midges

Biting midges are small robust insects with piercing and sucking mouthparts that belong to the family of flies Ceratopogonidae. Only a few groups within this family are known to suck blood and their distribution is almost world wide. These small flies are renowned for their nuisance biting associated with habitats such as coastal lagoons, estuaries, mangrove swamps and tidal flats. In Australia these flies are commonly known as sandflies but are correctly referred to as biting midges. The biting activity of adult biting midges is mainly limited to the periods of dawn and dusk; they will remain inactive through very windy weather, finding shelter amongst vegetation. Biting midges will usually disperse only short distances from their breeding sites. Only female midges feed on blood, but both the females and males will feed on vegetable fluids and nectar. Adults midges are 1.5-4.0 mm long with stout short legs, and at rest fold their wings, which are often mottled, over the abdomen. Their mouthparts are short and projected down. Female midges may attack humans in large numbers, biting on any areas of exposed skin, and often on the face, scalp and hands. Some species will blood feed on a wide range of animal hosts. The egg batches contain between 30-100 eggs, and are laid on selected substrates such as mud, decaying leaf litter, damp soil or other vegetative materials, dependent on the species. The small eel-like larvae hatch in a few days; their larval habitat must contain a proportion of organic material with a high moisture content to provide optimum conditions for the larval stage to thrive and pupate. The whole life cycle takes 3-10 weeks, dependent on species and environmental conditions, particularly temperature.

Clinical Presentation

Biting midges are responsible for acute discomfort, irritation and severe local reactions. Itching may commence immediately after the bite, but often not for some hours later, and most individuals are unaware of being bitten at the time. Biting midges have their greatest impact on people arriving to an area or tourists. Local residents seem to build up some immunity to the biting. In some sensitive people, midges can produce persistent reactions that blister and weep serum from the site of each bite and these reactions may last for several days to weeks. Biting midges are not known to transmit any disease-causing pathogens to humans in Australia. Biting midges are extremely annoying, but none are known to transmit disease agents to humans in the U.S. They have a much greater impact on non-human animals, both as biting pests and vectors of disease agents. In North America, the most important disease agent transmitted by biting midges is Blue Tongue virus. This virus is a major cause of disease in livestock in the western U. S., but it does not infect humans. The bites of biting midges inflict a burning sensation and can cause different reactions in humans, ranging from a small reddish welt at the bite site to local allergic reactions that cause significant itching. When numerous, biting midges have a real impact on residents and visitors of the Atlantic Coast, Gulf Coast, San Francisco Bay region, and southwestern deserts, primarily by limiting outdoor activities. Biting midge is a common name for pest species, but it is not the only one. For example, “no-see-ums” is used widely in the North America, “punkies” in the Northeast, “five-O’s (related to biting around 5 PM) in Florida and Alabama, “pinyon gnats” in the Southwest, and “moose flies” in Canada.

Biting Midge Female Blood Meal after Mating and Disease to Livestock

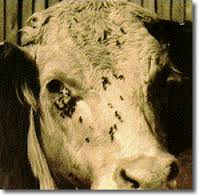

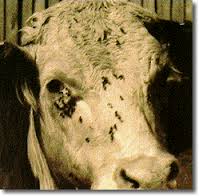

Stable Flies, Horn Flies, Deer Flies, Bot Flies attack Livestock

Stable Flies, Horn Flies, Deer Flies, Bot Flies attack Livestock

Stable Fly

stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans), a species of vicious bloodsucking fly in the family Muscidae (sometimes placed in the family Stomoxyidae) in the fly order, Diptera. Stable flies are usually found in open sunny areas, although they may enter a house during bad weather. Often known as biting houseflies, they may transmit anthrax and other animal diseases.

Introduction

The stable fly is a blood-sucking filth fly of considerable importance to people, pets, and the livestock live stock industry in Ohio. Filth flies, including stable flies, exploit habitats and food sources created by human activities, such as farming. “Stable fly” is just one of the mans common names used to refer to this pest. Stable flies are also known as “dog flies” because the fly often bites and irritates dogs. Other names are “lawn mower fly," because the larvae are often found in the cut grass on the undersides of lawn mowers, and the “biting house fly.” Stable flies primarily attack animals for a blood meal, but in the absence of an animal host, they will bite people. In its normal environment the stable fly is not considered a pest to humans. However, certain regions of the United States have considerable problems with large numbers of stable flies attacking people.

Biology

Stable flies breed in soggy hay, grasses or feed; piles of moist, fermenting weed or grass cuttings; spilled green chop; peanut litter; seaweed deposits along beaches; soiled straw bedding; and sometimes in hay ring feeding sites when the temperatures warm in the spring. The female, when depositing eggs, will often crawl into loose material. Each female fly may lay 500–600 eggs in four separate batches. Eggs are small, white, and sausage-shaped. Eggs hatch in 2–5 days into larvae, which feed and mature in 14–26 days. Larvae are typical maggots and transform to small, reddish-brown, capsule-like pupae from which the

adult flies emerge. The average life cycle is 28 days, ranging from 22–58 days depending on the weather conditions. In Ohio, during years with wet summers, the stable fly breeds throughout the year, although peak populations occur from October through January.

The stable fly adult is similar to the house fly in size and color. Adult stable flies are typically 5–7 mm in length and unlike the house fly, which has an un-patterned abdomen, stable fly abdomens have seven circular spots. Stable flies also have long, bayonet-like mouthparts for sucking blood. Unlike many other blood feeding fly species, both male and female stable flies feed on blood. Stable flies feed mainly on the legs of cattle and horses. Stable flies are competent fliers and have been shown to disperse far from their breeding sites to feed. Recent studies in Ohio have shown that the majority of stable flies collected at horse facilities were travelling between 0.8 and 1.5 km from cattle farms, following a blood meal, to breed in horse farms. One study even recorded stable flies travelling distances of up to 70 miles from their breeding sites. They are inactive at night, resting on fences, buildings, trees, and bushes.

Scope of the Problem in Ohio

Stable flies attack people, pets, and agricultural animals throughout Ohio. Stable fly bites are extremely painful to both people and animals. When hungry, stable flies are quite persistent and will continue to pursue a blood meal even after being swatted several times. Although the bite is painful, there is little irritation after the bite, and few people exhibit allergic reaction. Because stable flies are active during the daylight hours, the flies have a big impact in Ohio. The animal industries of Ohio are severely affected by the stable fly. Because the fly takes blood meals, animals are weakened from blood loss and continual irritation. Animals such as swine, cattle, and horses show reduced weight gains. As a result of stable fly annoyance, animals stamp nervously, switch, become irritable and have been known to stand in water, with only their necks and heads exposed, to escape the biting flies during heavy outbreaks. Stable flies also are known to transmit the pathogens that cause diseases such as anthrax, equine infectious anemia (EIA), and anaplasmosis to animals. In addition, bite wounds can be sites for secondary infection.

Because these pests leave an animal immediately after feeding, they may go unnoticed unless heavy outbreaks occur. Monitoring is important for early detection of a potential outbreak situation and is usually done by counting flies on lower legs of cattle and horses. Counts should be done on all four legs of at least 15 animals. Greater than 10 flies per animal is considered economically damaging. High numbers of stable flies on animals suggests a productive local breeding site. However, it is important to note that the absence of a local breeding site does not necessarily mean that the animals are not being bothered by stable flies. Because stable flies will disperse from breeding sites and travel great distances to obtain a blood meal, breeding sites may be over 1 kilometer away. Consequently, a stable fly breeding site on your property may have an influence on the people and animals for miles around. A study of horse facilities in Ohio found that only 24.3% of the flies captured on horse farms had fed on horses; 64.6% had travelled up to 1.5 km from cattle farms to reach the horse farms, with 9.5% of these having fed on humans.

While one stable fly does not cause significant damage, 50–100 of these blood-sucking pests occurring together with 500 horn flies can cause a substantial daily loss of blood. This common livestock pest situation can result in a loss of 10–20% in milk production and up to 40 pounds of beef gain eliminated per animal each year—an economic loss of millions of dollars per year

to Ohio cattlemen. Recent estimates give a total impact to the U.S. cattle industry of $2.211 billion per year, with $360 million for dairy, $358 million for calf-cattle herds, $1.268 billion for pastured cattle and $226 million for cattle on feed.

Control at Breeding Sites

The most practical and economical method for reducing stable fly populations is the elimination or appropriate management of breeding sources. It is important to remember that flies cannot develop in dry materials. Furthermore, due to the dispersal capability of stable flies, breeding sites on your property may be causing problems for other animals that may be miles away or in

residential areas where the flies feed on humans and pets. Management of potential breeding sites should be completed for the health and safety of your animals, your neighbors’ animals, and the local community. Most of the following methods also will reduce the presence of other localized fly problems through improved sanitation and hygiene.

Stable flies breed in the following types of material:

Green Chop or Silage- Stable fly maggots thrive in decaying plant material, such as old silage in and around feed troughs and trench silos. Silage probably has a greater potential for producing stable flies than almost any other material found on today's farms. More than 3,000 stable fly maggots per cubic foot of silage have been found in mid-January on some west Florida farms, and five times that number in late summer.

Crop residues - Unwanted crop residues, such as peanut vines discarded in piles during harvest, are frequently important sources of fly breeding. To avoid creating a breeding site, this material should be spread thinly for quick drying.

Hay and grain - Hay allowed to accumulate where animals are fed in fields decays rapidly when exposed to the elements and may produce flies in tremendous numbers. To prevent this source of fly breeding, feed cattle at a different place in the field each time so that accumulations of old hay do not occur. Likewise, spilled grain around feed troughs or storage bins may provide the stable fly with a moist, favorable breeding medium and should be cleaned up immediately.

Animal manures - When handled properly, manure need not breed stable flies at all. lt should not be allowed to accumulate for more than a week before it is spread thinly on fields, where quick drying eliminates stable fly breeding.

Stables - The popularity of pleasure horses creates a staggering number of fly breeding sources. However, proper care and management of waste feed and manure can greatly reduce or eliminate fly populations in these areas. Stalls should be cleaned of droppings daily and the manure spread thinly (not more than 1–2 inches deep). The choice of bedding is very important. Hay or straw absorbs urine and decomposes rapidly, and unless it is changed every few days, it will produce thousands of flies. A far better material is wood shavings, which, when cleaned of manure daily and changed approximately every two weeks, will not

normally breed flies.

Nuisance Flies Effect Livestock Animals and Animal Quarters

Horse Fly

Horse Fly

Horse and Deer Fly

Horse flies and Deer flies are bloodsucking insects that can be serious pests of cattle, horses, and humans. Horse flies range in size from 3/4 to 1-1/4 inches long and usually have clear or solidly colored wings and brightly colored eyes. Deer flies, which commonly bite humans, are smaller with dark bands across the wings and colored eyes similar to those of horse flies. Attack by a few of these persistent flies can make outdoor work and recreation miserable. The numbers of flies and the intensity of their attack vary from year to year. Numerous painful bites from large populations of these flies can reduce milk production from dairy and beef cattle and interfere with grazing of cattle and horses because animals under attack will bunch together. Animals may even injure themselves as they run to escape these flies. Blood loss can be significant. In a USDA Bulletin 1218, Webb and Wells estimated that horse flies would consume 1cc of blood for their meal, and they calculated that 20 to 30 flies feeding for 6 hours would take 20 teaspoons. This would amount to one quart of blood in 10 days. Female horse flies and deer flies are active during the day. These flies apparently are attracted to such things as movement, shiny surfaces, carbon dioxide, and warmth. Once on a host, they use their knife-like mouthparts to slice the skin and feed on the blood pool that is created. Bites can be very painful and there may be an allergic reaction to the salivary secretions released by the insects as they feed. The irritation and swelling from bites usually disappears in a day or so. However, secondary infections may occur when bites are scratched. General first aid-type skin creams may help to relieve the pain from bites. In rare instances, there may be allergic reactions involving hives and wheezing. Male flies feed on nectar and are of no consequence as animal pests. Horse flies and deer flies are intermittent feeders. Their painful bites generally elicit a response from the victim so the fly is forced to move to another host. Consequently, they may be mechanical vectors of some animal and human diseases.

LIFE CYCLE

The larvae of horse fly and deer fly species develop in the mud along pond edges or stream banks, wetlands, or seepage areas. Some are aquatic and a few develop in relatively dry soil. Females lay batches of 25 to 1,000 eggs on vegetation that stand over water or wet sites. The larvae that hatch from these eggs fall to the ground and feed upon decaying organic matter or small organisms in the soil or water. The larvae, stage usually lasts from one to three years, depending on the species. Mature larvae crawl to drier areas to pupate and ultimately emerge as adults.

PROTECTING YOURSELF

Deer flies are usually active for specific periods of time during the summer. When outside, repellents such as Deet and Off(N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) can provide several hours of protection. Follow label instructions because some people can develop allergies with repeated use, look for age restrictions. Permethrin-based repellents are for application to clothing only but typically provide a longer period of protection. Repellents can prevent flies from landing or cause them to leave before feeding but the factors that attract them (movement, carbon dioxide, etc.) are still present. These flies will continue to swarm around even after a treatment is applied. Light colored clothing and protective mesh outdoor wear may be of some value in reducing annoyance from biting flies. In extreme cases, hats with mesh face and neck veils and neckerchiefs may add some protection.

PROTECTING ANIMALS

Horse flies and deer flies can be serious nuisances around swimming pools. They may be attracted by the shiny surface of the water or by movement of the swimmers. There are no effective recommendations to reduce this problem. Permethrin-based sprays are labeled for application to livestock and horses. These insecticides are very irritating to the flies and cause them to leave almost immediately after landing. Often, the flies are not in contact with the insecticide long enough to be killed so they continue to be an annoyance. These flies will swarm persistently around animals and feed where the spray coverage was not complete (underbelly or legs) or where it has worn off. Repeated applications may be needed. Check the label about minimum retreatment intervals. Pyrethrin sprays also are effective but do not last as long as permethrin. Horse flies and deer flies like sunny areas and usually will not enter barns or deep shade. If animals have access to protection during the day, they can escape the constant attack of these annoying pests. They can graze at night when the flies are not active.

Deer Fly, Horn Fly, and Face Fly Nuisance to Livestock and Humans

Black Fly or Buffalo Gnat

Black flies, known also as "buffalo gnats" and "turkey gnats," are very small, robust flies that are annoying biting pests of wildlife, livestock, poultry, and humans. Their blood-sucking habits also raise concerns about possible transmission of disease agents. You are encouraged to learn more about the biology of black flies so that you can be better informed about avoiding being bitten and about their public health risk. Black flies can be annoying biting pests, but none are known to transmit disease agents to humans in the U. S. However, they transmit one parasitic nematode worm that infects humans in other regions of the world. Onchocerca volvulus causes a significant human disease known as

onchocerciasis or "river blindness." The bites of black flies cause different reactions in humans, ranging from a small puncture wound where the original blood meal was taken to a swelling that can be the size of a golf ball. Reactions to black fly bites that collectively are known as "black fly fever" include headache, nausea, fever, and swollen lymph nodes in the neck. In eastern North America, only about six black fly species are known to feed on humans. Several other species are attracted to humans, but they typically do not bite. However, the non-biting species fly around the head and may crawl into the ears, eyes, nose, or mouth, causing extreme annoyance to anyone engaged in outdoor activities. Black flies can be found throughout most of the U. S., but their impact on outdoor activities varies depending on the specific region and time of year. For example, in parts of the upper Midwest and the Northeast, black fly biting can be so extreme, especially in late spring into early summer, it may disrupt or prevent outdoor activities such as hiking, fishing, and kayaking. Besides being a nuisance to humans, black flies can pose a threat to livestock. They are capable of transmitting a number of different disease agents to livestock, including protozoa and nematode worms, none of which cause disease in humans. In addition to being vectors of disease agents, black flies pose other threats to livestock. For example, when numerous enough, black flies have caused suffocation by crawling into the nose and throat of pastured animals. On rare occasions, black flies have been known to cause exsanguination (death due to blood loss) from extreme rates of biting. Saliva injected by biting black flies can cause a condition known as "toxic shock" in livestock and poultry, which may result in death.

The Life Cycle of Black Flies

Black flies undergo a type of development known as "complete metamorphosis." This means the last larval stage molts into a non-feeding pupal stage that eventually transforms into a winged adult. After taking a blood meal, females develop a single batch of 200-500 eggs. Most species lay their eggs in or on flowing water, but some attach them to wet surfaces such as blades of aquatic grasses. The length of time it takes an egg to hatch varies greatly from species to species. Eggs of most species hatch in 4-30 days,

but those of certain species may not hatch for a period of several months or longer. The number of larval stages ranges from 4-9, with 7 being the usual number. The duration of larval development ranges from 1-6 months, depending in part on water temperature and food supply. The life cycle stage that passes though winter is the last stage larva attached underwater to rocks, driftwood, and concrete surfaces such as dams and sides of man-made channels.The pupal stage is formed the following spring or summer, typically in the same site as the last stage larva, but may occur downstream following larval "drift" with the current. Adults emerge from the pupal stage in 4-7 days and can live for a few weeks. Adults of most species are active from mid-May to July. The number of generations completed in one year varies among species, with some having only one generation, but most species that are major pests complete several generations per year. Black fly larvae and pupae develop in flowing water, typically non-polluted water with a high level of dissolved oxygen. Suitable aquatic habitats for black fly larval development vary greatly and include large rivers, icy mountain streams, trickling creeks, and waterfalls. Larvae of most species typically are found in only one of these habitats. Larvae remain attached to stationary objects in flowing water, held on by silken threads extruded from glands located at the end of the bulbous abdomen. Depending on species, mature larvae range from 5-15 mm in length and may be brown, green, gray, or nearly black in color. They possess a large head that bears two prominent structures known as "labral fans" that project forward. Labral fans are the primary feeding structures, filtering organic matter or small invertebrates out of the water current. Pupae remain attached to stationary objects in flowing water as well. They typically are orange and appear mummy-like because the developing wings and legs are tightly attached to the body. Pupae of many species produce a delicate, silken "cocoon" of varying density, weave, and size that partially or nearly entirely encloses them; other species produce hardly any cocoon at all.

What Should I Know About the Feeding Habits of Adult Black

Flies?

It is estimated that females of 90% of the black fly species require a blood meal for the development of eggs. Those of most species feed on mammals, while others feed on birds. Females of some black fly species feed on only one host, whereas others are known to feed on over 30 different host species. No North American species feed exclusively on humans. Male black flies are not attracted to humans, and their mouthparts are not capable of biting. Females of most species of black flies feed during the day, usually biting on the upper body and head. Unlike certain species of mosquitoes and biting midges, black flies do not enter human structures to seek blood meals.

Black Fly Bite to Humans and Animals

Cat Flea

Cat Flea

Cat Flea and Dog Flea

What Are Fleas?

With nearly 2,000 species and subspecies, fleas thrive in warm, humid environments, and feed on the blood of their hosts. Dogs play host to the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), whose dark brown or black body is usually one to three millimeters in length.

Why Are Dogs Susceptible to Fleas?

Fleas are hearty and nimble, and when searching for a host, they can jump 10,000 times in a row (the length of three football fields). Three pairs of legs make for excellent leaping capabilities (up to two feet), and a laterally flattened body allows for quick movement in a dog’s fur. With a complete life cycle ranging anywhere from 16 days to 21 months, depending on environmental conditions, fleas are most commonly found on a dog’s abdomen, the base of the tail and the head. With heavy infestations, however, fleas can thrive anywhere on the body. They feed once every day or two, and generally remain on their host during the interim.

What Are Some Signs of Fleas in Dogs?

Droppings or “flea dirt” in a dog’s coat - Flea eggs on dog or in dog’s environment - Allergic dermatitis - Excessive scratching, licking or biting at skin - Hair loss - Scabs and hot spots - Pale gums - Tapeworms.

What Are Some Complications of Fleas in

Dogs?

Since fleas can consume 15 times their own body weight in blood, they can cause anemia or a significant amount of blood loss over time. This is especially problematic in young puppies, where an inadequate number of red blood cells can be life-threatening to some dogs. Signs of parasitic anemia include pale gums, cold body temperature and listlessness. When a dog has a heightened sensitivity to the saliva of fleas, just one bite of a flea can cause an allergic reaction. This condition is known as flea allergy dermatitis and causes intense itching and discomfort for your dog. Signs include generalized hair loss, reddened skin, scabs and hot spots. Flea allergy dermatitis often leads to skin infections.

Are Certain Dogs Prone to Fleas?

Dogs who live in warm, humid climates, where fleas thrive at temperatures of 65 to 80 degrees, and those who live outdoors are most vulnerable to fleas.

What Should I Do If I Think My Dog Has Fleas?

Consult your veterinarian, who will confirm the diagnosis and discuss appropriate treatment options. It is important to tailor your treatment to your pet and his environment, since certain products in combination can be toxic. Your veterinarian can also determine the best plan for preventing fleas in the future.

How Do I Treat Fleas?

It is important that all of your pets are treated for fleas, including indoor and outdoor cats, and that the environment is treated as well. Speak with your veterinarian about choosing the right flea treatment product. Common options include a topical, liquid treatment applied to the back of the neck, shampoos, sprays and powders. Some products kill both adult fleas and their eggs, but they can vary in efficacy. It is very important not to use products on your dog that are intended for cats (and vice versa). Prescription products are generally more effective and safer than over-the-counter products. Thoroughly clean your house, including rugs, bedding and upholstery. (Remember to discard any vacuum bags.) In severe cases, you might consider using a spray or fogger, which requires temporary evacuation of the home.

How Can I Prevent Fleas?

Using a flea comb on your dog and washing his bedding once a week will go a long way toward controlling flea infestation. Also, it is important to treat your yard as thoroughly as your house. Concentrate on shady areas, where fleas live, and use an insecticide or nematodes, microscopic worms that kill flea larvae.

Identifying the problem

Adult cat fleas are about 1/8 inch long (1 to 3 mm). They are brownish-black, flattened looking, and without wings. Backward-pointing bristles help fleas move through the hairs or feathers of host animals and make them more difficult to remove by grooming. The six legs, especially the hind pair, are long and adapted for jumping. Flea larvae are less than 1/4 inch long (6 mm), legless, and dirty white in color. The most likely place to find larvae is in infested pet bedding.

Understanding fleas