New York Black Rat Eating Fruit

New York Black Rat Eating Fruit

Black Rats, Norway and Roof Rat

Welcome to 'New York RIP' (that's RAT Information Portal): Map marks the blocks with the worst infestations... and you’ll want to avoid the areas colored red New York's Health Department provides an interactive map for residents to view rat infestations on RIP The Rat Information Portal collates all the city's rat data for residents to view. The city is notorious for its rats, which are estimated be at levels twice the human population. Residents can view the rat infestation history of buildings and neighborhoods as well as action taken. The very keen can attend the New York City Health Department's Rodent Academy to learn about rat control.

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2545033/Welcome-RIP-New-Yorks-Rat-Information-Portal-charts-areas-densest-infestations-youll-want-avoid-buildings-marked-red-like-plague.html#ixzz360ioPgeh

The popular and informational television station Animal Planet has named New York City the worst city for rats in the world. In this case, they are not referring to politicians. We are talking about “Rattus norvegicus,” otherwise known as the "brown rat." Brown rats are a scourge to rural and urban areas and are one of the most serious pests on the planet, carrying diseases and multiplying at exponential speed. One pair of rats can multiply up to 200 times in just one year. They are adept at climbing, swimming, and yes, working their way thru a serpentine of sewer pipes and exiting your toilet bowl. It is estimated that NYC has twice as many rats as they do humans. If you run the math, that would total about 16 million rats. But no worries, the New York's Health Department provides an interactive map for residents to view rat infestations on RIP (Rat Informational Portal). The series of maps mark the blocks with the worst infestations, coloring the most densely infested areas with red. As a result, one can look at raw data and investigate any neighborhood or building to see to what extent any particular venue is infested. Clicking on an area of the map will supply inspection dates, actions, and results. Moreover, one can retrieve rat history, going back to 2009, of any address within New York’s five boroughs. Maybe most disturbing, according to author Robert Sullivan, is that there are more rats infected with bubonic plague in North America than there were in Europe at the time of the Black Death. By some estimates, up to 50% of Europe’s population was decimated due to the pestilence that swept Italy and other European countries during the middle ages. Sullivan adds, “A third of the world’s food supply is consumed or destroyed by rats. Rats have eaten cadavers in the New York City coroner’s office. Rats have attacked and killed homeless people sleeping on the streets of Manhattan.” Moreover, Sullivan claims, “The Department of Homeland Security, as part of its post-9/11 bioterror-alertness effort, catches rats and inspects their fleas to see if terrorists have released the Black Death in New York City. A male rat will continue mating with a female rat even if she’s dead. A ‘dominant male rat may mate with up to twenty female rats in just six hours.'”

Rat Life Cycle

Ears & hearing: Thick, opaque, short with fine hairs. Length of ear: 20-22mm. Excellent sense of hearing.

Eyes & sight: Small. Poor sight, color blind.

Snout, smell and taste: Blunt & rounded, excellent sense of smell and taste

Droppings: in groups, but sometimes scattered. Ellipsoidal capsule shaped, about 20mm long.

Habits & habitat:

Does burrow. Lives outdoors, indoors and in sewers. Domestic environment, Farms, Refuse tips, Sewers, Urban waterways, Warehouses, Hedgerows. Nests in burrows. Can climb, though not agile. Very good swimmer. Conservative, somewhat predictable in habit. Will avoid unfamiliar objects, e.g. bait trays, placed on runs, for some days. Need to gnaw to keep their constantly growing incisor teeth worn down. Creatures of habit; will leave regular runs to & from feeding areas.

Feeding habits:

Omnivorous, more likely to eat meat than Rattus rattus. Consumes up to 30 grams per day, drinks water or eats food with high water content. Will hoard food for future consumption. Most likely to eat at night. Range 50 metres when looking for food. A separate water supply is required. Rats cannot survive on water in food alone.

Life cycle: 9-18 months

Sexual maturity: 2-3 months

Litter size: 8-10 offspring

Maximum reproduction rate:7 litters per year

Roof Rats Rattus rattus

Pest Stats Color: Brown with black intermixed; Gray, white or black underside

Legs: 4

Shape: Long and thin with scaly tail; large ears and eyes

Size: 16" total (6-8" body plus 6-8" tail)

Antennae: No

Region: Coastal states and the southern third of the U.S.

What are roof rats? Roof rats – also called black rats or ship rats – are smaller than Norway rats, but cause similar issues. This rodent gets its name from its tendency to be found in the upper parts of buildings. The roof rat is thought to be of Southeast Asian origin, but is now found throughout the world, especially in tropical regions.

Habits

Roof rats are primarily nocturnal. They forage for food in groups of up to ten and tend to return to the same food source time after time. These rats follow the same pathway between their nest and food.

Habitat

Roof rats live in colonies and prefer to nest in the upper parts of buildings. They can also be found under, in and around structures.

Threats

Roof rats secured their place in history by spreading the highly dangerous bubonic plague. Though transmission is rare today, there are still a handful of cases in the U.S. each year. Roof rats can also carry fleas and spread diseases such as typhus, jaundice, rat-bite fever, trichinosis and salmonellosis.

Norway Rats

Pest Stats Color: Brown with scattered black hairs; gray to white underside

Legs: 4

Shape: Long, heavily bodied; blunt muzzle

Size: 7-9 ½ inches long

Antennae: No

Region: Found throughout U.S.

Norway rats are believed to be of Asian origin, but are now found throughout the world. These rats can cause damage to properties and structures through their gnawing. Norway rats have smaller eyes and ears and shorter tails.

Habits

Norway rats are primarily nocturnal and often enter a home in the fall when outside food sources become scarce. These rats are known to gnaw through almost anything – including plastic or lead pipes – to obtain food or water. Norway rats are social rodents and build burrows close to one another.

Habitat

Outdoors, Norway rats live in fields, farmlands and in structures. These rats frequently burrow in soil near riverbanks, in garbage and woodpiles, and under concrete slabs. Indoors, Norway rats often nest in basements, piles of debris or undisturbed materials. Rodents can gain entry to a home through a hole the size of a quarter.

Threats

Norway rats can cause damage to structures through their gnawing and eating. These rats are also vectors of diseases including plague, jaundice, rat-bite fever, cowpox virus, trichinosis and salmonellosis. In addition, Norway rats can contaminate food and introduce fleas into a home.

Deer Mice

Deer Mice Peromyscus maniculatus, The deer mouse is found in rural areas and rarely invades residential homes. Deer mice are of medical concern because they are common carriers of Hantavirus. Rodents can be difficult to keep out of structures. Mice can squeeze through spaces as small as a dime and rats can fit through holes the size of a quarter. For proper rodent pest control, seal any cracks and voids. Ensure there is proper drainage at the foundation and always install gutters or diverts which will channel water away from the building.

Pest Stats Color: Brown, with white feet and underbelly

Legs: 4

Shape: Round

Size: 5 to 8 inches long

Antennae: No

Region:Found throughout U.S.

Habits

The deer mouse prefers the outdoors.

Habitat

The deer mouse makes its home outdoors. Sheltered areas such as hollow tree logs or piles of debris make the ideal deer mouse habitat. On the rare occasions the deer mouse comes indoors, it prefers undisturbed areas such as attics.

Threats

The deer mouse transmits the potentially fatal Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome.

The disease can be transmitted through contact with mouse carcasses, or by

breathing in aerosolized urine droplets of infected deer mice.

House Mice

House Mice Mus domesticus, The house mouse is the most common rodent pest in most parts of the world. It can breed rapidly and adapt quickly to changing conditions. In fact, a female house mouse can give birth to a half dozen babies every three weeks,and can produce up to 35 young per year.

Pest Stats Color: Dusty gray with a cream belly

Legs: 4

Shape: Round

Size: 2 1/2 - 3 3/4" long

Antennae: No

Region: Found throughout U.S.

Habits

House mice prefer to eat seeds and insects, but will eat many kinds of food. They are excellent climbers and can jump up to a foot high, however, they are color blind and cannot see clearly beyond six inches.

Habitat

House mice live in structures, but they can survive outdoors, too. House mice prefer to nest in dark, secluded areas and often build nests out of paper products, cotton, packing materials, wall insulation and fabrics.

Threats

Micro droplets of mouse urine can cause allergies in children. Mice can also bring fleas, mites, ticks and lice into your home.

House Mouse:

Description & Life Cycle

There are two species of mice commonly found in homes and buildings:

House Mouse; which is small, dark grey/brown, longish tail and very common in both urban and rural areas. Long Tailed Field Mouse; which is a prettier mouse with a very long tail, large black eyes, yellowish/brown coat with pale a white underside and it is most common in rural areas. We will deal with the house mouse, being most common overall, and both species can be controlled in the same way.

Life cycle:

gestation is about 19-21 days

average litter size of 6-8

5-10 litters per year, young reach sexual maturity in 6-8 weeks, average life span in the wild is under one year due to heavy predation.

Signs of infestation:

Small mouse dropping about 3-6mm long; look like grains of black rice usually lots of evidence of things they have been chewing like insulation, pipes, cables, timber and paper tooth marks on food, usually with the rice sized black droppings alongside baseboards and under cabinets.

Deer Mice Peromyscus maniculatus, The deer mouse is found in rural areas and rarely invades residential homes. Deer mice are of medical concern because they are common carriers of Hantavirus. Rodents can be difficult to keep out of structures. Mice can squeeze through spaces as small as a dime and rats can fit through holes the size of a quarter. For proper rodent pest control, seal any cracks and voids. Ensure there is proper drainage at the foundation and always install gutters or diverts which will channel water away from the building.

Pest Stats Color: Brown, with white feet and underbelly

Legs: 4

Shape: Round

Size: 5 to 8 inches long

Antennae: No

Region:Found throughout U.S.

Habits

The deer mouse prefers the outdoors.

Habitat

The deer mouse makes its home outdoors. Sheltered areas such as hollow tree logs or piles of debris make the ideal deer mouse habitat. On the rare occasions the deer mouse comes indoors, it prefers undisturbed areas such as attics.

Threats

The deer mouse transmits the potentially fatal Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome.

The disease can be transmitted through contact with mouse carcasses, or by

breathing in aerosolized urine droplets of infected deer mice.

House Mice

House Mice Mus domesticus, The house mouse is the most common rodent pest in most parts of the world. It can breed rapidly and adapt quickly to changing conditions. In fact, a female house mouse can give birth to a half dozen babies every three weeks,and can produce up to 35 young per year.

Pest Stats Color: Dusty gray with a cream belly

Legs: 4

Shape: Round

Size: 2 1/2 - 3 3/4" long

Antennae: No

Region: Found throughout U.S.

Habits

House mice prefer to eat seeds and insects, but will eat many kinds of food. They are excellent climbers and can jump up to a foot high, however, they are color blind and cannot see clearly beyond six inches.

Habitat

House mice live in structures, but they can survive outdoors, too. House mice prefer to nest in dark, secluded areas and often build nests out of paper products, cotton, packing materials, wall insulation and fabrics.

Threats

Micro droplets of mouse urine can cause allergies in children. Mice can also bring fleas, mites, ticks and lice into your home.

House Mouse:

Description & Life Cycle

There are two species of mice commonly found in homes and buildings:

House Mouse; which is small, dark grey/brown, longish tail and very common in both urban and rural areas. Long Tailed Field Mouse; which is a prettier mouse with a very long tail, large black eyes, yellowish/brown coat with pale a white underside and it is most common in rural areas. We will deal with the house mouse, being most common overall, and both species can be controlled in the same way.

Life cycle:

gestation is about 19-21 days

average litter size of 6-8

5-10 litters per year, young reach sexual maturity in 6-8 weeks, average life span in the wild is under one year due to heavy predation.

Signs of infestation:

Small mouse dropping about 3-6mm long; look like grains of black rice usually lots of evidence of things they have been chewing like insulation, pipes, cables, timber and paper tooth marks on food, usually with the rice sized black droppings alongside baseboards and under cabinets.

Pocket Gopher

Description:

Pocket gophers are fossorial rodents named for their fur-lined cheek pouches. Their cheek pouches, or pockets, are used for transporting bits of plant food that they gather while foraging underground. They have special adaptations for their burrowing lifestyle, including clawed front paws for digging, small eyes and ears, and sensitive whiskers and tails. They’re also able to close their lips behind their long incisors so that they can use their teeth to loosen soil without getting any dirt in their mouths.

Size:

Pocket gophers are medium-sized rodents that range in length from 5 to 14 inches.

Diet:

Roots, tubers, and the occasional aboveground plant provide all the necessary nutrients to these hungry rodents. Pocket gopher teeth are well-adapted for their vegetarian diet. Their incisors are ever-growing, which compensates for the tooth wear incurred while chewing on hard, gritty materials. Pocket gophers also have flattened molars and premolars which are perfect for grinding vegetation. They are the only natural force that seems to be able to limit the growthe of quaking aspen--they can chew the root systems back faster than they can grow back.

Predation:

Pocket gophers face numerous threats from predators. They are eaten by animals that are able to follow them into burrows, such as weasels and snakes. Canines and badgers dig them out of the ground, and if pocket gophers leave their tunnels, owls and hawks are happy to snatch them up.

Typical Lifespan:

Pocket gophers generally live less than three years, which is typical for small rodents.

Habitat:

Loose, sandy soil with edible plant cover is the best habitat for pocket gophers. Often, this means that pocket gophers make their homes in lawns and crop fields, much to the dismay of homeowners and farmers. Voracious pocket gophers can leave unsightly dirt mounds in yards, and they readily feed on ornamental garden plants. In their native range, however, pocket gophers are beneficial components of ecosystems. They move enormous amounts of earth every year, and therefore help to aerate the soil. This is especially important when soil has been compacted by grazing livestock or agricultural machinery. The tunnels also serve to capture snowmelt and rainfall that would otherwise run over the soil surface and cause erosion. Abandoned tunnels provide habitat for a number of other species, and the waste left behind by pocket gophers fertilizes the soil.

U.S. Range:

The most widespread North American species is the plains pocket gopher, which is found throughout the Great Plains region.

Several other species are found in the West and Southeast.

Life History and Reproduction:

Pocket gophers are solitary animals that only come together in the spring and summer to breed. Young pocket gophers are born in nest chambers underground. The mother takes care of the young for several weeks before sending them on their way to construct burrows of their own.

Fun Fact:

Pocket gophers are sometimes confused with their fossorial relatives, moles. There are several easy ways to tell the two groups

apart. Moles have small teeth and tiny, unapparent eyes. Pocket gophers have long incisors that protrude from the mouth, and their eyes are easy to see. Secondly, mole tunnels leave raised ridges in the ground, whereas pocket gopher tunnels do not.

Conservation Status:

Most pocket gopher species are relatively common and not of conservation concern. The desert pocket gopher is the most threatened species, because it occupies a very small range and is thus more vulnerable to habitat loss.

Description:

Pocket gophers are fossorial rodents named for their fur-lined cheek pouches. Their cheek pouches, or pockets, are used for transporting bits of plant food that they gather while foraging underground. They have special adaptations for their burrowing lifestyle, including clawed front paws for digging, small eyes and ears, and sensitive whiskers and tails. They’re also able to close their lips behind their long incisors so that they can use their teeth to loosen soil without getting any dirt in their mouths.

Size:

Pocket gophers are medium-sized rodents that range in length from 5 to 14 inches.

Diet:

Roots, tubers, and the occasional aboveground plant provide all the necessary nutrients to these hungry rodents. Pocket gopher teeth are well-adapted for their vegetarian diet. Their incisors are ever-growing, which compensates for the tooth wear incurred while chewing on hard, gritty materials. Pocket gophers also have flattened molars and premolars which are perfect for grinding vegetation. They are the only natural force that seems to be able to limit the growthe of quaking aspen--they can chew the root systems back faster than they can grow back.

Predation:

Pocket gophers face numerous threats from predators. They are eaten by animals that are able to follow them into burrows, such as weasels and snakes. Canines and badgers dig them out of the ground, and if pocket gophers leave their tunnels, owls and hawks are happy to snatch them up.

Typical Lifespan:

Pocket gophers generally live less than three years, which is typical for small rodents.

Habitat:

Loose, sandy soil with edible plant cover is the best habitat for pocket gophers. Often, this means that pocket gophers make their homes in lawns and crop fields, much to the dismay of homeowners and farmers. Voracious pocket gophers can leave unsightly dirt mounds in yards, and they readily feed on ornamental garden plants. In their native range, however, pocket gophers are beneficial components of ecosystems. They move enormous amounts of earth every year, and therefore help to aerate the soil. This is especially important when soil has been compacted by grazing livestock or agricultural machinery. The tunnels also serve to capture snowmelt and rainfall that would otherwise run over the soil surface and cause erosion. Abandoned tunnels provide habitat for a number of other species, and the waste left behind by pocket gophers fertilizes the soil.

U.S. Range:

The most widespread North American species is the plains pocket gopher, which is found throughout the Great Plains region.

Several other species are found in the West and Southeast.

Life History and Reproduction:

Pocket gophers are solitary animals that only come together in the spring and summer to breed. Young pocket gophers are born in nest chambers underground. The mother takes care of the young for several weeks before sending them on their way to construct burrows of their own.

Fun Fact:

Pocket gophers are sometimes confused with their fossorial relatives, moles. There are several easy ways to tell the two groups

apart. Moles have small teeth and tiny, unapparent eyes. Pocket gophers have long incisors that protrude from the mouth, and their eyes are easy to see. Secondly, mole tunnels leave raised ridges in the ground, whereas pocket gopher tunnels do not.

Conservation Status:

Most pocket gopher species are relatively common and not of conservation concern. The desert pocket gopher is the most threatened species, because it occupies a very small range and is thus more vulnerable to habitat loss.

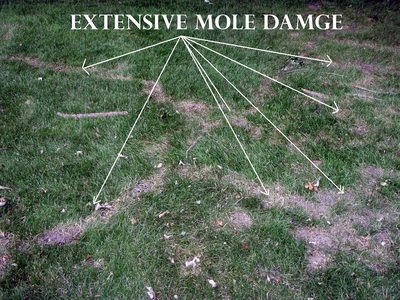

Moles

Family: Talpidae (moles) in the order Insectivora

Description:

Chipmunk-sized, though not a rodent; has palmlike, short front feet that are

held over the head with palms facing outward. The mole uses its large hands to

move through the soil in about the same way a person swims underwater. The head looks nearly featureless except for the flexible, piglike snout. Although the mole’s eyes are only good for telling light from dark, its senses of hearing, touch and smell are acute. The velvety fur is characteristically slate gray but often appears silvery on fleshly groomed moles and sooty black on juveniles. A cinnamon-brown staining on the chin and along the middle of the belly is common on adults. The tail is nearly naked and is highly sensitive to touch.

Size:

Males :

Average total length, 7 inches (17.6 cm) Average length of tail, 1 1/4 inches (3.3 cm) Average weight, 4 ounces (115 g)

Females:

Average total length, 6 5/8 inches (16.8 cm) Average length of tail, 1 1/4 inches (3.3 cm) Average weight, 3 ounces (85 g).

Total length: 5½–8 inches; tail length: ¾–1½ inches; weight: 1–5 ounces.

Habitat and conservation:

Moles live in a series of tunnels underground and may be found wherever the soil is sufficiently thick, pliable and adhesive enough to support a tunnel system and is adequately populated with grubs, earthworms and other prey items. In most cases it is not necessary to manage moles; to ensure healthy soils, their presence should be tolerated. When their presence cannot be tolerated at all, traps are usually the most effective way to control them.

Foods:

Grubs and earthworms constitute the bulk of their diet. They also prey on other soil-dwelling creatures such as beetles, spiders, centipedes, ant pupae and cutworms. In fact, a mole can harvest more than 140 grubs and cutworms daily (many of which are destructive to your backyard plants). Moles can eat half their body weight a day!

Distribution in Missouri: Statewide.

Status: Common.

Life cycle:

Each mole has its own system of tunnels and lives a solitary life. They are active day and night, resting for 3 hours, then becoming active again for 5 hours. Moles breed in late winter or spring and have a gestation period of about 4–6 weeks. Single annual litters of 2–5 young are born in March, April or May. Young moles are born naked and helpless, but growth and development is rapid. About 4 weeks after birth, they leave the nest and fend for themselves.

Human connections:

Though moles are routinely disliked for disfiguring lawns and inadvertently damaging plant roots, their tunneling also aerates and mixes soil, permitting air and moisture to penetrate deeper. They also eat many destructive insects such as cutworms and Japanese beetle larvae.

Ecosystem connections:

Their digging and tunneling makes soils healthier, and their feeding on insects helps keep those populations in check. And although living underground offers some protection, moles still fall prey to snakes, hawks, owls, skunks, coyotes and foxes. The mole discussed here is usually referred to as the eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus). It is an insectivore, not a rodent, and is related to shrews and bats. True moles may be distinguished from meadow mice (voles), shrews, or pocket gophers—with which they are often confused—by noting certain characteristics. They have a hairless, pointed snout extending nearly 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) in front of the mouth opening. The small eyes and the opening of the ear canal are concealed in the fur; there are no external ears. The forefeet are very large and broad, with palms wider than they are long. The toes are webbed to the base of the claws, which are broad and depressed. The hind feet are small and narrow, with slender, sharp claws.

Family: Talpidae (moles) in the order Insectivora

Description:

Chipmunk-sized, though not a rodent; has palmlike, short front feet that are

held over the head with palms facing outward. The mole uses its large hands to

move through the soil in about the same way a person swims underwater. The head looks nearly featureless except for the flexible, piglike snout. Although the mole’s eyes are only good for telling light from dark, its senses of hearing, touch and smell are acute. The velvety fur is characteristically slate gray but often appears silvery on fleshly groomed moles and sooty black on juveniles. A cinnamon-brown staining on the chin and along the middle of the belly is common on adults. The tail is nearly naked and is highly sensitive to touch.

Size:

Males :

Average total length, 7 inches (17.6 cm) Average length of tail, 1 1/4 inches (3.3 cm) Average weight, 4 ounces (115 g)

Females:

Average total length, 6 5/8 inches (16.8 cm) Average length of tail, 1 1/4 inches (3.3 cm) Average weight, 3 ounces (85 g).

Total length: 5½–8 inches; tail length: ¾–1½ inches; weight: 1–5 ounces.

Habitat and conservation:

Moles live in a series of tunnels underground and may be found wherever the soil is sufficiently thick, pliable and adhesive enough to support a tunnel system and is adequately populated with grubs, earthworms and other prey items. In most cases it is not necessary to manage moles; to ensure healthy soils, their presence should be tolerated. When their presence cannot be tolerated at all, traps are usually the most effective way to control them.

Foods:

Grubs and earthworms constitute the bulk of their diet. They also prey on other soil-dwelling creatures such as beetles, spiders, centipedes, ant pupae and cutworms. In fact, a mole can harvest more than 140 grubs and cutworms daily (many of which are destructive to your backyard plants). Moles can eat half their body weight a day!

Distribution in Missouri: Statewide.

Status: Common.

Life cycle:

Each mole has its own system of tunnels and lives a solitary life. They are active day and night, resting for 3 hours, then becoming active again for 5 hours. Moles breed in late winter or spring and have a gestation period of about 4–6 weeks. Single annual litters of 2–5 young are born in March, April or May. Young moles are born naked and helpless, but growth and development is rapid. About 4 weeks after birth, they leave the nest and fend for themselves.

Human connections:

Though moles are routinely disliked for disfiguring lawns and inadvertently damaging plant roots, their tunneling also aerates and mixes soil, permitting air and moisture to penetrate deeper. They also eat many destructive insects such as cutworms and Japanese beetle larvae.

Ecosystem connections:

Their digging and tunneling makes soils healthier, and their feeding on insects helps keep those populations in check. And although living underground offers some protection, moles still fall prey to snakes, hawks, owls, skunks, coyotes and foxes. The mole discussed here is usually referred to as the eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus). It is an insectivore, not a rodent, and is related to shrews and bats. True moles may be distinguished from meadow mice (voles), shrews, or pocket gophers—with which they are often confused—by noting certain characteristics. They have a hairless, pointed snout extending nearly 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) in front of the mouth opening. The small eyes and the opening of the ear canal are concealed in the fur; there are no external ears. The forefeet are very large and broad, with palms wider than they are long. The toes are webbed to the base of the claws, which are broad and depressed. The hind feet are small and narrow, with slender, sharp claws.

Voles

APPEARANCE:

Voles range in length from 3-1/2 to 7 in. (9-18 cm) and have rounded bodies with gray or brown coats, blunt muzzles, small ears concealed in the long fur, and short tails.

INFESTATIONS/HABITAT:

Voles can live in small colonies of a few or larger colonies of up to 300 individuals. They usually live in grass meadows where they build distinctive runways which crisscross the area. They also dig underground burrows where they construct food and nesting chambers.

DIET:

Voles are scavengers, they will eat anything they think they can. Species such as the meadow vole that are mainly found in grassy agricultural land are seen as a pest as they eat and damage crops and also eat plants and ruin lawns in gardens.

LIFE CYCLE/REPRODUCTION:

Vole numbers fluctuate from year to year; under favorable conditions their populations can increase rapidly. Voles may breed at any time of year, but their peak breeding period is in spring. Female Voles mature in 35 to 40 days and can have up to five to ten litters per year.

TYPES OF DAMAGE/DISEASE:

Typical Vole damage in Wisconsin is loss of mature and young trees and shrubs during winter, as well as pathways worn down in lawns from constant travel. Voles can cause extensive damage to trees, shrubs, orchards and ornamental plants by girdling trees and shrubs. They prefer the bark of young trees but will attack any tree, regardless of age, when food is scarce. They may damage trees as high as the snow accumulates and may also harm Christmas trees stacked after cutting, making vole control crucial at this time of year.

MOLES AND VOLES COMMONLY CONFUSED:

One thing we run into is confusion between moles and voles. We do have moles in the state of Wisconsin, but not in the counties of Ozaukee, Washington, Waukesha, and Milwaukee.

APPEARANCE:

Voles range in length from 3-1/2 to 7 in. (9-18 cm) and have rounded bodies with gray or brown coats, blunt muzzles, small ears concealed in the long fur, and short tails.

INFESTATIONS/HABITAT:

Voles can live in small colonies of a few or larger colonies of up to 300 individuals. They usually live in grass meadows where they build distinctive runways which crisscross the area. They also dig underground burrows where they construct food and nesting chambers.

DIET:

Voles are scavengers, they will eat anything they think they can. Species such as the meadow vole that are mainly found in grassy agricultural land are seen as a pest as they eat and damage crops and also eat plants and ruin lawns in gardens.

LIFE CYCLE/REPRODUCTION:

Vole numbers fluctuate from year to year; under favorable conditions their populations can increase rapidly. Voles may breed at any time of year, but their peak breeding period is in spring. Female Voles mature in 35 to 40 days and can have up to five to ten litters per year.

TYPES OF DAMAGE/DISEASE:

Typical Vole damage in Wisconsin is loss of mature and young trees and shrubs during winter, as well as pathways worn down in lawns from constant travel. Voles can cause extensive damage to trees, shrubs, orchards and ornamental plants by girdling trees and shrubs. They prefer the bark of young trees but will attack any tree, regardless of age, when food is scarce. They may damage trees as high as the snow accumulates and may also harm Christmas trees stacked after cutting, making vole control crucial at this time of year.

MOLES AND VOLES COMMONLY CONFUSED:

One thing we run into is confusion between moles and voles. We do have moles in the state of Wisconsin, but not in the counties of Ozaukee, Washington, Waukesha, and Milwaukee.

Ground Squirrel

Ground Squirrel

Chipmunk or Ground Squirrel

Chipmunks typically inhabit woodlands, but they also inhabit areas in and around rural and suburban homes. In large numbers, they can cause structural damage by burrowing under patios, stairs, retention walls, or foundations. They also may eat flower bulbs, seeds, or seedlings. This fact sheet discusses chipmunk biology and explores ways to control damage caused by chipmunks. The eastern chipmunk is a small, brown, burrow-dwelling squirrel. It typically measures 5 to 6 inches long and weighs about 3 ounces. It has two tan and five blackish longitudinal stripes on its back, and two tan and two brownish stripes on each side of its face. The longitudinal stripes end at the reddish rump. The tail is 3 to 4 inches long and is hairy but not bushy. Chipmunks sometimes are confused with red squirrels. Chipmunks are very vocal and emit a rather sharp “chuck-chuck-chuck” call. The red squirrel also is very vocal but has a high-pitched chatter. Red squirrels spend a great deal of time in trees; chipmunks, although they can climb trees, spend most of their time on the ground.

General Biology

Eastern chipmunks typically inhabit mature woodlands and woodlot edges, but they also inhabit areas in and around suburban and rural homes. Chipmunks are most active during the early morning and late afternoon. Population densities of chipmunks are typically two to four animals per acre, although densities may be as high as ten animals per acre if sufficient food and cover are available. The home range of a chipmunk may be up to ½ acre, but adult animals defend a territory only about 50 feet around their burrow entrance. Consequently, home ranges often overlap among individuals.

Diet

The diet of chipmunks consists primarily of grains, nuts, berries, seeds, mushrooms, insects, and carrion. Chipmunks also prey on young birds and bird eggs. Chipmunks spend most of their time on the ground, but regularly climb trees in the fall to gather nuts, fruits, and seeds. Chipmunks cache food in their burrows throughout the year. By storing and scattering seeds, they promote the growth of various plants.

Habitat

Chipmunk burrows often are well hidden near objects or buildings (for example, stumps, wood or brush piles, basements, and garages). The burrow entrance usually is about 2 inches in diameter and is not surrounded by obvious mounds of dirt, because the chipmunk carries the dirt in its cheek pouches and scatters it away from the burrow. In most cases, the burrow’s main tunnel is 20 to 30 feet long. Complex burrow systems occur where cover is sparse, and normally include a nesting chamber, one or two food storage chambers, various side pockets connected to the main tunnel, and separate escape tunnels. With the onset of cold weather during late fall, chipmunks enter a period of inactivity that continues through the winter months. They do not enter a true hibernation as woodchucks do during the fall, but instead rely on the cache of food they store in their burrows. Some individuals become active on warm, sunny winter days. In Ohio and Pennsylvania, chipmunks emerge from their burrows from late April to early May, although they can be observed above ground in early March during a brief breeding season. Chipmunks mate two times a year, in early spring and again early in the summer. After a 31-day gestation period, they give birth to two to five young in April to May and again in August to October. The young are sexually mature within one year. Adults may live up to three years in the wild.

Damage Control

Damage Identification

Chipmunks present in large numbers can cause structural damage by burrowing under patios, stairs, retention walls, or foundations. They also may consume flower bulbs, seeds, or seedlings, as well as bird or grass seed and pet food not stored in rodent-proof containers.

Exclusion

Exclude chipmunks from buildings wherever possible. Use caulking, hardware cloth with ¼-inch mesh, or other appropriate materials to close openings where chipmunks could gain entry. Hardware cloth also may be used to exclude chipmunks from flower beds. Seeds and bulbs can be covered by ¼-inch hardware cloth, and the cloth itself should be covered with soil. The cloth should extend at least 1 foot past each margin of the planting. Where high populations of chipmunks exist, exclusion often is less expensive than trapping.

Habitat Modification

Where chipmunks are a problem, landscaping features, such as ground cover trees, and shrubs should not be planted continuously connecting wooded areas with the foundations of homes. Cover provides protection for chipmunks that may attempt to gain access to the home. It also is difficult to detect chipmunk burrows that are adjacent to foundations when wood piles, debris, or ground cover plantings provide above-ground protection. To prevent spilled bird seed from attracting and supporting chipmunks near homes, place bird feeders at least 15 to 30 feet from buildings. Keeping the grass cut short around the edges of buildings will provide less cover for the chipmunks and cause them to use the area less frequently.

Chipmunks typically inhabit woodlands, but they also inhabit areas in and around rural and suburban homes. In large numbers, they can cause structural damage by burrowing under patios, stairs, retention walls, or foundations. They also may eat flower bulbs, seeds, or seedlings. This fact sheet discusses chipmunk biology and explores ways to control damage caused by chipmunks. The eastern chipmunk is a small, brown, burrow-dwelling squirrel. It typically measures 5 to 6 inches long and weighs about 3 ounces. It has two tan and five blackish longitudinal stripes on its back, and two tan and two brownish stripes on each side of its face. The longitudinal stripes end at the reddish rump. The tail is 3 to 4 inches long and is hairy but not bushy. Chipmunks sometimes are confused with red squirrels. Chipmunks are very vocal and emit a rather sharp “chuck-chuck-chuck” call. The red squirrel also is very vocal but has a high-pitched chatter. Red squirrels spend a great deal of time in trees; chipmunks, although they can climb trees, spend most of their time on the ground.

General Biology

Eastern chipmunks typically inhabit mature woodlands and woodlot edges, but they also inhabit areas in and around suburban and rural homes. Chipmunks are most active during the early morning and late afternoon. Population densities of chipmunks are typically two to four animals per acre, although densities may be as high as ten animals per acre if sufficient food and cover are available. The home range of a chipmunk may be up to ½ acre, but adult animals defend a territory only about 50 feet around their burrow entrance. Consequently, home ranges often overlap among individuals.

Diet

The diet of chipmunks consists primarily of grains, nuts, berries, seeds, mushrooms, insects, and carrion. Chipmunks also prey on young birds and bird eggs. Chipmunks spend most of their time on the ground, but regularly climb trees in the fall to gather nuts, fruits, and seeds. Chipmunks cache food in their burrows throughout the year. By storing and scattering seeds, they promote the growth of various plants.

Habitat

Chipmunk burrows often are well hidden near objects or buildings (for example, stumps, wood or brush piles, basements, and garages). The burrow entrance usually is about 2 inches in diameter and is not surrounded by obvious mounds of dirt, because the chipmunk carries the dirt in its cheek pouches and scatters it away from the burrow. In most cases, the burrow’s main tunnel is 20 to 30 feet long. Complex burrow systems occur where cover is sparse, and normally include a nesting chamber, one or two food storage chambers, various side pockets connected to the main tunnel, and separate escape tunnels. With the onset of cold weather during late fall, chipmunks enter a period of inactivity that continues through the winter months. They do not enter a true hibernation as woodchucks do during the fall, but instead rely on the cache of food they store in their burrows. Some individuals become active on warm, sunny winter days. In Ohio and Pennsylvania, chipmunks emerge from their burrows from late April to early May, although they can be observed above ground in early March during a brief breeding season. Chipmunks mate two times a year, in early spring and again early in the summer. After a 31-day gestation period, they give birth to two to five young in April to May and again in August to October. The young are sexually mature within one year. Adults may live up to three years in the wild.

Damage Control

Damage Identification

Chipmunks present in large numbers can cause structural damage by burrowing under patios, stairs, retention walls, or foundations. They also may consume flower bulbs, seeds, or seedlings, as well as bird or grass seed and pet food not stored in rodent-proof containers.

Exclusion

Exclude chipmunks from buildings wherever possible. Use caulking, hardware cloth with ¼-inch mesh, or other appropriate materials to close openings where chipmunks could gain entry. Hardware cloth also may be used to exclude chipmunks from flower beds. Seeds and bulbs can be covered by ¼-inch hardware cloth, and the cloth itself should be covered with soil. The cloth should extend at least 1 foot past each margin of the planting. Where high populations of chipmunks exist, exclusion often is less expensive than trapping.

Habitat Modification

Where chipmunks are a problem, landscaping features, such as ground cover trees, and shrubs should not be planted continuously connecting wooded areas with the foundations of homes. Cover provides protection for chipmunks that may attempt to gain access to the home. It also is difficult to detect chipmunk burrows that are adjacent to foundations when wood piles, debris, or ground cover plantings provide above-ground protection. To prevent spilled bird seed from attracting and supporting chipmunks near homes, place bird feeders at least 15 to 30 feet from buildings. Keeping the grass cut short around the edges of buildings will provide less cover for the chipmunks and cause them to use the area less frequently.

Aabate Termite & Pest Control, Contact Us @ 937 718 6560 for Service